Foreward and Forward: Rebirthing Emmanuel Magazine

Michael E. DeSanctis, Editor

In a recent installment of SSS Grapevine, I introduced myself as editor of the newly-launched digital version of Emmanuel Magazine. By means of the “foreward” that follows, I hope to offer both longtime readers and prospective new ones a fuller sense of my plans for the publication as it springs back to life after lying dormant for several years. It’s no secret that Catholic periodical literature in this country has fallen on hard times. In the past six months alone, several publications once fixtures in American Catholic households have simply ceased to be, victims, to be sure, of declining subscription numbers but also of a downward shift in interest concerning mainstream religion that shows little sign of improving anytime soon. Never one to shrink from a challenge, however, and reinforced by the fear-negating effects of eucharistic prayer from which I personally draw great sustenance, I regard this as good a moment as any to pursue new means of delivering Emmanuel to its readership. The effort currently underway to make the magazine an open-access feature of the SSS website will likely please the many members and associates of the Congregation who’ve long dreamt of such a thing. A dream no longer, except as concerns the loftiness of its goals, Emmanuel Magazine joins the many other publications, religious or otherwise, to have traded a delivery system dependent on ink and paper for one that uses the screens of readers’ electronic devices as its point of meeting with them. In this it remains true to the attitudes of Congregation founder St. Peter Julian Eymard (1811-68), who was quick to employ any magic of communication at his disposal to imake the Christ of the Eucharist pertinent to people of his day.

In a recent installment of SSS Grapevine, I introduced myself as editor of the newly-launched digital version of Emmanuel Magazine. By means of the “foreward” that follows, I hope to offer both longtime readers and prospective new ones a fuller sense of my plans for the publication as it springs back to life after lying dormant for several years. It’s no secret that Catholic periodical literature in this country has fallen on hard times. In the past six months alone, several publications once fixtures in American Catholic households have simply ceased to be, victims, to be sure, of declining subscription numbers but also of a downward shift in interest concerning mainstream religion that shows little sign of improving anytime soon. Never one to shrink from a challenge, however, and reinforced by the fear-negating effects of eucharistic prayer from which I personally draw great sustenance, I regard this as good a moment as any to pursue new means of delivering Emmanuel to its readership. The effort currently underway to make the magazine an open-access feature of the SSS website will likely please the many members and associates of the Congregation who’ve long dreamt of such a thing. A dream no longer, except as concerns the loftiness of its goals, Emmanuel Magazine joins the many other publications, religious or otherwise, to have traded a delivery system dependent on ink and paper for one that uses the screens of readers’ electronic devices as its point of meeting with them. In this it remains true to the attitudes of Congregation founder St. Peter Julian Eymard (1811-68), who was quick to employ any magic of communication at his disposal to imake the Christ of the Eucharist pertinent to people of his day.

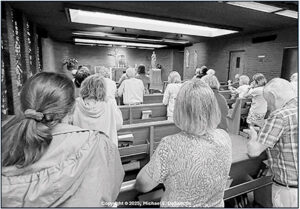

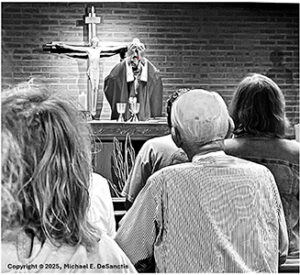

There’s an image that runs through my devotional routine at church most weekday mornings, just before eight o’clock Mass is about to begin. A prayer aid of sorts from some undisclosed part of my imagination, it consists of a small container—a lidded cigar box, perhaps, but nothing fancier—filled with polished rocks, bits of jewelry and other glittery objects I take to be precious, each representing someone whose needs I’m prompted to place upon the altar beside the bread and wine that are the priest’s business. It’s no small collection, given that my wife, the souls of our parents, my four adult children and their spouses all claim places there. The intentions of those with whom I bear no blood relation at all likewise make it into the box, including the handful of “Daily Massers” who encircle me like grace each morning and carry about them signs of joy or sorrow or gratitude I recognize in an instant as my own.

The imagery I describe may well have been borrowed from young Jem and Scout Finch, the brother-and-sister characters in To Kill a Mockingbird, whose own cigar box-treasury of objects is treated with such cinematic reverence in the title sequence of the 1962 Universal Pictures version of Harper Lee’s famous novel. The film is one of my favorites, partly because of the way it reminds me that even the commonest of objects can assume the life-changing power of sacraments. I’m referring here to the way in which the Finch children come upon items placed for them in the hollow of a tree by an elusive figure named Boo Radley. To Boo, who remains unseen throughout the film until its dramatic conclusion, they’re tokens of friendship worthy of preservation within the womb-like opening the tree provides, a shinboku you might call it in the context of Japanese Shintoism or a so-called “Asherah pole” if referencing ancient Canaanite religion. To the Catholic imagination, Boo’s tree-shrine evokes the idea of a tabernacle or one of those pedimented votive shrines that so frequently adorn the facades of private homes and other buildings throughout, say, Catholic Italy. The same applies to the box in which the Finch children preserve their tangible traces of Boo’s goodness. It, too, is a sacrarium, as the Ancient Romans might have used the term, its contents so rare and rarified as to deserve containment something akin to a safe deposit box.

The imagery I describe may well have been borrowed from young Jem and Scout Finch, the brother-and-sister characters in To Kill a Mockingbird, whose own cigar box-treasury of objects is treated with such cinematic reverence in the title sequence of the 1962 Universal Pictures version of Harper Lee’s famous novel. The film is one of my favorites, partly because of the way it reminds me that even the commonest of objects can assume the life-changing power of sacraments. I’m referring here to the way in which the Finch children come upon items placed for them in the hollow of a tree by an elusive figure named Boo Radley. To Boo, who remains unseen throughout the film until its dramatic conclusion, they’re tokens of friendship worthy of preservation within the womb-like opening the tree provides, a shinboku you might call it in the context of Japanese Shintoism or a so-called “Asherah pole” if referencing ancient Canaanite religion. To the Catholic imagination, Boo’s tree-shrine evokes the idea of a tabernacle or one of those pedimented votive shrines that so frequently adorn the facades of private homes and other buildings throughout, say, Catholic Italy. The same applies to the box in which the Finch children preserve their tangible traces of Boo’s goodness. It, too, is a sacrarium, as the Ancient Romans might have used the term, its contents so rare and rarified as to deserve containment something akin to a safe deposit box.

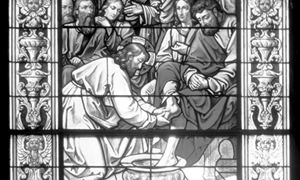

In my case, I’m convinced, the Holy Spirit is the unseen gift giver who’s working overtime to help my thoroughly Catholic subconscious preserve the names and needs of those I love from ending up in the same place I’ve left my car keys or the half-dozen other details of my life—both mental and material—that nowadays escape my mind with alarming regularity. On one level, at least, it can be said that the whole of the church’s sacramental treatment of worldly experience is mnemonic, a means of helping its members bring to mind who they truly are with the help of objects and gestures it has had good reason to enshrine for centuries. All the “do this in remenbrancing” we resort to at Jesus’ very command in the course of any celebration of the Eucharist, certainly, reflects our fondness for looking backward in time to review the ways God has moved through the twists and turns of sacred history on our behalf. Even the most ardently antiquarian of us, however, knows that the past doesn’t tell the whole story of who and whose we are. We’re destined for a celestial home with our Creator unfettered even by the limits of time or space or earthly perception. Ours is a forward-looking and anticipatory relationship with the world, as surely as it’s inescapably tradition-bound.

All of this is to say that in assuming editorship of Emmanuel Magazine, a beloved print publication of the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament for decades now being recast in digital form, I hope to maintain a habit of looking backward and forward with equal regularity. The truth is that Emmanuel has enjoyed a reputation for providing members of the Congregation and its associates with commentary on the eucahristic life free of any ideological slant, fad or fashion likely to obscure its underlying message. As a former academic theologian who’s been acquainted with the magazine since the 1990s, I’ve personally valued its straightforward treatment of topics meant to deepen the church’s understanding of what it’s doing when assembled for worship at ambo and altar, a sentiment echoed not long ago by a diocesan priest-friend of mine and longtime Emmanuel subscriber during a conversation we shared. “I used to love that little magazine,” he told me before describing how saddened he was in 2021 to learn of its discontinuation. My friend went on to say that what he appreciated most about Emmanuel was its balanced presentation of worship-related topics that, in the hands of other Catholic publications, might be used as a pretext for promoting one or another side in the so-called “culture wars” that continue to dog the church.

I hope to maintain a habit of looking backward and forward with equal regularity. The truth is that Emmanuel has enjoyed a reputation for providing members of the Congregation and its associates with commentary on the eucahristic life that’s elevated in tone and free of any ideological slant, fad or fashion likely to obscure its underlying mission.

This is not to suggest that Emmanuel itself hasn’t been provocative in its own way when necessary—though “responsibly prophetic” might be a better way to describe the stance it’s taken on a wide range of issues. Some time ago, for example, under the editorship of the late Father Anthony Scheuller, SSS (1950-2021), an article of my own entitled “Curates and Curators at the Altar: How the New Clericalism Hurts Liturgical Renewal” appeared in the magazine. The piece described how some younger clergy in the U.S. with no personal memory of liturgical practice prior to Vatican II (1962-65) were taking it upon themselves to undo any liturgical instruction of the council with which they did not personally agree. My observations struck a chord with Emmanuel subscribers and gained wider attention when I was subsequently interviewed about my views by the National Catholic Reporter (NCR), a newspaper generally characterized by those Catholic observers with any wit for such things as “left-leaning.” The editors of NCR wished to make a digital link to my original article available to their readers, a request Father Schueller and his Emmanuel staff were only too happy to accommodate.

The willingness to assist others in imitation of the same Suffering Servant we encounter in the Eucharist was not a charism exclusive to “Father Tony,” as he was often called, but seems to have possessed all of those who’ve occupied the editor’s desk at Emmauel since its founding in 1895 by Most Rev. Bishop Camillus Paul Maes (1846-1915), Bishop of Covington, Ohio. During a recent tour of the Emmanuel Media Resources warehouse operated by the Congregation in the Highland Heights suburb of Cleveland, Ohio, where hardcopies of Emmanuel Magazine going back for decades are archived, I was struck by what these men had achieved sheerly in terms of output. What my mind knew of their work from histories of the publication I’d scoured, my eyes confirmed by quick estimate of the volume of shelf space that had been required to preserve the physical traces of its extraordinarily long lifespan. The facility was absolutely still throughout my visit and carried the unmistakable scent of ink on paper one normally associates with libraries. In a sense it was a library, as the label is broadly applied to any place made to house items of value. To my admittedly fertile imagination, it also bore the quality of temple architecture, filled from floor to ceiling with the ghosts of all those writers since Bishop Maes’ time who’d had something important to say in the pages of Emmanuel about the church’s most precious method of worship.

It’s precisely to these writers and editors from the publication’s past—not to mention the countless readers they touched through their contributions—that I now feel such responsibility while facilitating its relocation from shelf to (electronic) showcase. At its new home on the Congregation’s website, the magazine will mimic Boo Radley’s chosen site for gift giving and and human connection as portrayed on film, a spot where regular passers-by might find an item or two waiting for them to make their own. Its purpose will be less to titillate than to educate, however, which is not to say it won’t display the same concern for outward appearance that characterized Emmanuel throughout its time in print. Any publication committed to celebrating an action of the church for which beauty is an expressed requirement (Sacrosanctum concilium, 122), it seems to me, should likewise embody some measure of that same virtue. “Devotion begets depiction,” I used to remind both the budding art historians and theologians who alternately filled my classroom at the Catholic university where I was once a professor, which, for a publication as explicitly sacramental in focus as Emmanuel, provides reason enough to engage the senses of its readers as much as their minds.

It’s precisely to these writers and editors from the publication’s past—not to mention the countless readers they touched through their contributions—that I now feel such responsibility while facilitating its relocation from shelf to (electronic) showcase. At its new home on the Congregation’s website, the magazine will mimic Boo Radley’s place of gift giving and communion as portrayed on film, a spot where regular passers-by might find an item or two waiting for them to make their own.

The magazine’s reemergence within a media landscape increasingly awash in misinformation or content tailored to the narrowest of audiences leads me to stress my desire to keep Emmanuel a source of commentary on the Eucharist broad in ideology and appeal but always moored to the church’s normative approach to liturgical practice. Nowadays, especially, with episcopal legislation pertinent to sacred liturgy at the universal, territorial and diocesan levels fully available online to any interested party, there should be no question as to how the church wishes its members to believe and behave when praying as members of the assembled Mystical Body. If, as our new pope, Leo XIV, stated in his May 18, 2025, inaugural Mass homily, the Christian community is to serve as a “small leaven of unity, communion and fraternity within the world,” the furtherance of its own cohesion must be a goal of every Big Leaven event we presume to call our “Heavenly Banquet.” It’s to grappling with the mystery of this sublime action in the name of ecclesial unity that Emmanuel Magazine reenvisioned in electronic form will be committed.

While continuing to serve as a platform for contributing writers with academic or pastoral expertise in sacramental theology and related areas, the publication is prepared to highlight expressions of wisdom of a different sort drawn from the so-called sensus fidelium of lay members of the church, clergy and religious for whom life without the Eucharist would be unthinkable. There’s much of value to be found in the collective “sense of the faithful” the Catholic laity, ordered men or women and members of the secular priesthood together bring to the discussion of worship in our time. Corporate prayer is something the church has always thought and written about with the intent of clarifying its beliefs. Ultimately, however, it’s something we practice at Christ’s invitation within the lengths and limits of our particular circumstances. Under my watch, then, Emmanuel Magazine will continue to offer space to contributors eager to focus on the more practical facets of liturgy, as it did in the past through such regular features as “Breaking Bread,” “Eucharist and Culture” and “Pastoral Liturgy.”

Holding me to this promise without even knowing they are will be the members of the Daily Mass group in my parish with whom I began this essay. Its members routinely teach me a great deal about what it means to be a eucharistic people, either by exhibiting the steadfastness of believers considerably older than me or, in the case of at least one young, fellow worshiper about whom I’ve written elsewhere (see “Intergenerational relationships enrich parish life,” U.S. Catholic, March 2025, https://uscatholic.org/articles/202503/intergenerational-relationships-enrich-parish-life/), by demonstrating a facility with the language of prayer completely free of self-consciousness. A magazine named for a God dwelling amidst God’s people and revealed to them through the elements and actions of an ancient table ritual should be as attentive to the human side of the eucharistic equation as to that part we think of as purely divine. The so-called “horizontal dimension” of sacred worship, which of late is treated so disparagingly by certain voices in the church, discloses the humanity of Jesus in all its diversity while never diminishing the radical particularity of his self-immolation to the Father enacted at the altar.

I’m grateful to provincial superior Father John Thomas Lane, SSS, and his advisory council for entrusting me with the exciting work ahead. I’d also like to restate the invitation I made in my SSS Grapevine essay to anyone wishing to join me in nurturing Emmanuel back to life. I’m eager to know what you most liked about the magazine during its years in print and would we happy to review any written material you may wish to share with its readers related to the history, theology and practice of eucharistic prayer. Sacred liturgy being something that shrivels in a vacuum, the magazine’s policy will be to continue to accept book, movie and TV reviews, along with examples of poetry, photography and other forms of creative expression. All speak of the redemptive power of beauty and remind us of the seriousness with which we should take the “Sacrament of the World,” as theologian Karl Rahner (1904-84) was fond of calling it, marvelously grafted to the “Sacrament at the Altar” we normally reserve for our churches.

It might be best to think of Emmanuel Magazine’s five- or six-year absence from the scene as little more than a temporary “dormition,” like that such biblical figures as Abram (Genesis 15:12) or the young man the Book of Acts identifies as “Eutychus” (20: 7-12) undergo for their own good. It’s not a stretch to compare it to the hours of sleep-like stillness Jesus himself spent in a tomb before emerging from it utterly transformed. The publication’s simply undergone a dormant stage in its life-cycle, a chrysalis state of frozen animation that makes its return all the sweeter. The “morgue,” as some journalists still call that corner of a newsroom where dated materials are sent to molder, is no place for a periodical as full of fight for the cause of excellence in liturgical prayer as Emmanuel. Neither is a warehouse full of shelving units. It’s fixed to the digital windows on the world belonging to readers deeply in love with of the Eucharist, their feet firmly planted in the twenty-first century, that it belongs. Let this modest “Declaration of Purpose” represent a first step forward in realizing this vision and a reaffirmation of the role Emmanuel Magazine can play in the work of the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament.

It might be best to think of Emmanuel Magazine’s five- or six-year absence from the scene as little more than a temporary “dormition,” like that such biblical figures as Abram (Genesis 15:12) or the young man the Book of Acts identifies as “Eutychus” (20: 7-12) undergo for their own good. It’s not a stretch to compare it to the hours of sleep-like stillness Jesus himself spent in a tomb before emerging from it utterly transformed. The publication’s simply undergone a dormant stage in its life-cycle, a chrysalis state of frozen animation that makes its return all the sweeter. The “morgue,” as some journalists still call that corner of a newsroom where dated materials are sent to molder, is no place for a periodical as full of fight for the cause of excellence in liturgical prayer as Emmanuel. Neither is a warehouse full of shelving units. It’s fixed to the digital windows on the world belonging to readers deeply in love with of the Eucharist, their feet firmly planted in the twenty-first century, that it belongs. Let this modest “Declaration of Purpose” represent a first step forward in realizing this vision and a reaffirmation of the role Emmanuel Magazine can play in the work of the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament.

©2025 Emmanuel Magazine, Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament

All rights reserved.

Download a pdf version of this article here.

Readers may reach editor Michael E. DeSanctis at editor@blessedsacrament.com and by mail at Emmanuel Magazine, Editorial Office, 220 Seminole Dr., Erie, PA, 16505.